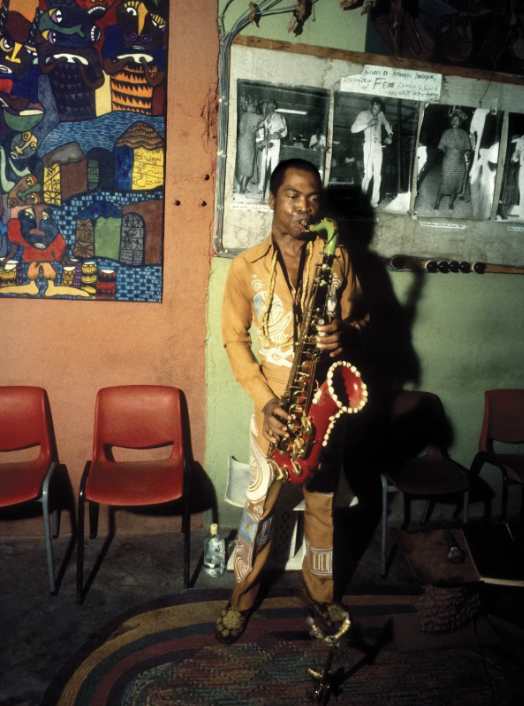

West African Icons: King Sunny Ade and Fela Kuti

Nate Appelbaum ’28 and Luke Brittson ’28

Hello BHSEC! We are Nate Appelbaum and Luke Brittson, and this is the first installment in our music column, in which we’ll introduce a new musical style or album or artist every time we have the chance to share with you. We’ll start off by talking about two very important West African and Nigerian musicians–Fela Kuti and King Sunny Ade. We’ll explore each of their most famous albums, Zombie (Coconut Records, 1976) and Juju Music (Island Records, 1982), both musically and with an eye on the social impact they had.

When listening to two landmark albums in the history of West African music–Fela Kuti’s “Zombie” and King Sunny Ade’s “Juju Music”, the first thing that struck me, and likely the first thing that will strike any listener, is the polyrhythms. On the first track–named after the album itself-— we hear at least 5 or 6 separate rhythms. The relaxed drumming or Tony Allen occupies space alongside grooving basslines, persistent and funky guitar similar to that of J.B’s, and auxiliary percussion from a shaker and cowbell. A vocal chorus also trades space with a full horn section, creating a layered listening experience. But this thriving and active rhythm section further compliments what pulses on top of it. Sweeping piano solos as well meandering but powerful horns are some highlights, especially the trumpet on “Zombie” and the saxophone on “Mister Follow Follow.” This is to take nothing away from Kuti’s voice itself, which has range within a single song that some artists can never accomplish across a whole career. Often, he starts out with a soft croon similar to that of Western pop artists of the 20th and 21st century. But he hardly stops or settles there. He rises to a hoarse shout, plateaus to a narrative similar to that of a spoken-word artist, and sometimes jumps to a falsetto for dramatic effect. Overall, this music is outstanding, brimming with energy and passion, as well as virtuosic and exciting musical ideas.

King Sunny Ade similarly leans into the polyrhythmic approach that defines West African music, but takes a markedly different approach to it than Fela–focusing much more on percussion than traditional melodic instruments. On the 3-minute track “Mo Beru Agba,” Ade is accompanied only by bass and at least 3-4 types of percussion, leading to a feeling that is at once spare and exciting, contrasting with Fela’s dense and pulsating rhythms. On “Ma Jaiye Oni,” Ade uses a more melodic approach that shares space with the complex percussion. The highlight of that tune is sudden stretches of solo guitar that seems to be melodic and employ finger-picking while simultaneously sounding like it would not be entirely out of place in George Clinton’s orchestra. This 3-minute solo is entirely elevated by the backing it shares–active, jumpy percussion which is itself elevated by laid-back, funky bass. So much music today seems desperate to force its ideas onto its listener as quickly as it can, which leads to repetitive, restrictive, and corporate-sounding music which are a byproduct of stale, boring beats. “Eje Nlo Gba Ara Mi,” my favorite track on the album, provides an antithesis to this music. Ade and his “African Beats” calmly let their musical ideas develop while not trying to force anything on anyone. If you’re listening, that’s great, but they could care less. As they play, they often circle back to the same musical ideas. But each time they do it, it sounds different. Maybe more or less emphasis is placed on the idea, or the backing rhythms are different, or a different group of musicians play it. That’s one of the many reasons this music is special and incredible.

This music is distinct because it is inspired by Western music, but it also draws on styles that once led to Western music. On Fela’s “Observation Is No Crime,” Allen’s drumming combined with the bassline of the tune sounds similar to the Chicago blues shuffle that formed the foundation for much of what the Stones and Beatles did, as well as countless other rock groups. The polyrhythms that were essential to Fela and Ade’s sound were emulated both directly by groups like the Talking Heads on “Remain in light,” but was more broadly part of a musical tradition through places like Congo Square that helped to create the “swing” sound and formed the foundation of jazz decades before the release of this music. But at the same time, the trumpet solo on the track draws heavy influences of Lee Morgan and Miles Davis, and the saxophone solo on “Mr. Follow Follow” sounds not entirely dissimilar to Sonny Rollin’s calypso era–or even his hard bop era. And as I’ve alluded to throughout, the guitar and rhythmic ideas in both of these artist’s work sounds very similar to pioneers of funk such as James Brown, Parliament-Funkadelic, or the Meters. So, one of the reasons this music is interesting is because of the special relationship it occupies with Western music.

We feel that it is also of importance to analyze the historical context and resulting factors of this album. As stated above, both albums are heavily inspired by western music, but also by western activism. Fela Kuti’s album *Zombie* (1976) is one of the most powerful political statements in African music, blending searing critique with infectious Afrobeat rhythms. Though deeply rooted in Nigerian socio-political realities, ‘Zombie’ also draws inspiration from global currents of protest music and Western activism, channeling revolutionary energy that resonated with civil rights, anti-imperialist, and anti-establishment movements worldwide. The title track, Zombie’ in Fela’s album, uses biting satire to liken Nigerian soldiers to brainless "zombies" who follow orders without thought. At the time, Nigeria was under a military regime, and Fela used this metaphor to expose the brutality, blind obedience, and corruption of the armed forces. “Zombie no go go, unless you tell am to go” mock the loss of personal agency, but could also expose the amount of brutality and corruption that there was, leading to a controlling fear around soldiers. This was a dangerous satire—so provocative that it led to a brutal military attack on Fela’s Kalakuta Republic commune in 1977.

Though ‘Zombie’ is a distinctly African protest record, focusing on African problems, its creation and message were shaped by Fela’s exposure to Western activism during his 1969 tour in the United States:

In L.A., Fela met Sandra Izsadore, a member of the Black Panther Party, who introduced him to the writings of Malcolm X, Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), and other radical thinkers.

This encounter was transformative and may have been a key catalyst for the album ‘Zombie in the first place.’ Before this, Fela was more focused on love songs and jazz-fusion; afterward, his music took on explicitly political and pan-African tones. (This change can be seen through his album ‘The 69’ Los Angeles Sessions compared to Zombie and Gentleman)

Fela began to see music as a tool of resistance, much like how James Brown’s ‘Say It Loud – I'm Black and I'm Proud’ or Gil Scott-Heron’s ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,’ which was influential not only because of its political message, but because of its musical uniqueness and legacy in hip-hop, spoken word poetry, and jazz.

"Music is the weapon of the future." – Fela Kuti

Sampling and Influence

What has ‘Zombie’ (the album) influenced or been sampled in? What is the importance of it?

“Fear Not of Man” – Mos Def, who name-checks Fela as a spiritual ancestor,

*“Kinda Like a Big Deal” – Clipse feat. Kanye West sampled Fela’s ‘Mr. Follow Follow,’ a song with similar themes to ‘Zombie,’ Beyoncé’s “End of Time” and Kendrick Lamar’s live performances have been inspired rhythmically by Afrobeat structures pioneered by Fela. Sampling or referencing Fela’s music signals political/oppressive resistance and Afrocentric pride. Musically, it brings polyrhythmic complexity, horn-driven energy, and hypnotic groove, which definitely deserves its place in the ‘industrialized’ music industry today. Politically, it pays homage to pan-African consciousness and a fearless critique of oppression.